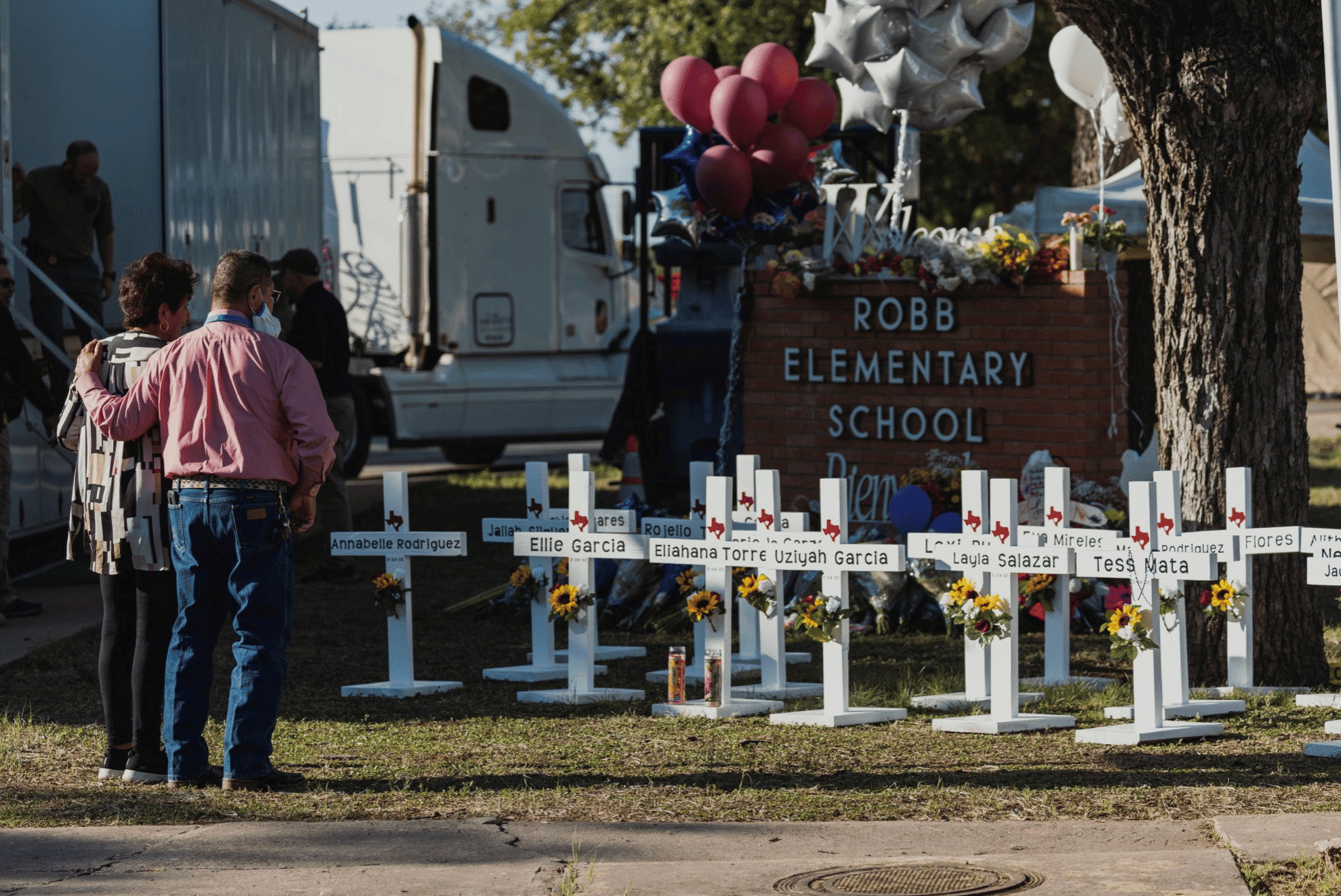

Buffalo, New York. Laguna Woods, California. Uvalde, Texas. In little more than a week, three more places have been added to a uniquely American geography of terror and grief.

In this shadow landscape, all the familiar features of a normal town are present – schools, places of worship, grocery stores, offices – but are here transformed into killing fields and memorials to unimaginable loss.

Each new addition to this grim map also brings a familiar ritual of public angst and political sloganeering. Politicians stand in front of television cameras and say the same things they said after the last massacre, while citizens take to social media and reuse the posts they’ve been sharing multiple times a year, for many years.

The numbing familiarity of those responses can provoke the hopeless conviction that American society is trapped in a perpetual cycle of horror.

The reality is that there are things that can be done, even in America’s polarized climate, to make these massacres – and the steady march of less publicized gun deaths that happen every day – less likely to occur.

UConn faculty members are at the forefront of doing the research and gathering the data needed to approach gun violence differently, and to craft real solutions to the problem.

‘We Think About This Almost Daily’

The most obvious – and most difficult – questions on gun violence often boil down to questions of policy. The UConn ARMS Center (Advancing Research, Methods, and Scholarship for Gun Injury Prevention), which includes the Gun Violence Prevention-Research Interest Group, connects scholars, advocates, and policymakers to seek solutions for reducing all forms of gun violence, ranging from mass shootings to suicide to accidental shootings.

Left to Right: Kerri Raissian, Lisa Singh, Amanda Crawford, Jeremy Stein, and David Pucino speak at a Gun Violence Misinformation Panel at the Hartford Times Building on April 5, 2022. (Contributed Photo)

The center uses research and data to guide its work, offering practical policy frameworks and solutions rooted in scholarship rather than politics. ARMS is housed within the Institute of Collaboration on Health, Intervention, and Policy (InCHIP) and is affiliated with the School of Public Policy in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

“Gun violence is a terrible social problem that every American has some contact with whether they want it or not,” says Kerri M. Raissian, associate professor of public policy and director of the ARMS Center. “Every American is at risk of experiencing gun injury or death, so this is a problem that transcends all of us.”

Raissian and Jennifer Necci Dineen, associate professor-in-residence of public policy and the center’s associate director, say they have three research projects underway, including a qualitative survey of 18 general practitioners nationwide to determine what might stop them from having discussions with their patients about safe gun storage.

The study sought nine doctors from states that have child access prevention requirements and nine from states that do not, Dineen says, to see if physicians think about the legal context when considering such a discussion during patient well-visits. Details from the survey are being looked at now.

Raissian and Dineen, along with Damion J. Grasso, associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at UConn School of Medicine, also just received the results of a second research project, this one surveying 2,000 Americans on how they perceive policy to regulate firearms and whether they see such proposals as harmful or beneficial to them.

“We’re trying to develop a tool that policymakers or community providers could use to assess whether stakeholders would perceive a policy as harmful or beneficial, with the thought that if they see it as harmful, they won’t buy into it,” Dineen says. For instance, “if a safe storage policy is viewed as being harmful, then it’s going to be difficult to get people to employ it.”

On Tuesday, that data made its way to researchers, which includes a partner from Johns Hopkins University, and during a meeting about the project they received news of the Texas shooting.

“We think about this literally almost daily,” Dineen says. “What happened in Texas was an overwhelming tragedy but there are parents who are losing their children every day, people losing their spouses, communities dealing with firearms deaths on a regular basis. This just makes us aware of how much communication work there is to do with the people who don’t think about it every day.”

The third project they’re working on uses the data from the national survey of Americans along with an additional 150 Missouri residents to consider that state’s attitudes toward its Second Amendment Preservation Act, which went into effect last year. With funding from the Missouri Foundation for Health, the study also includes 30 qualitative interviews with Missourians about the act, which allows people to sue if they feel police violated their Second Amendment rights, even if it was to protect themselves or others.

Uniting Scholarly Perspectives

ARMS brings together nearly two dozen researchers looking at the issue of gun violence, such as Amanda Crawford, assistant professor in journalism, who studies dissemination of misinformation in the context of mass shootings, and Peter Kochenburger, associate clinical professor of law and executive director of the Insurance Law Center, who’s an expert on liability insurance in the firearm industry.

The interest group has also taken a leading role in connecting scholars and policymakers, organizing a panel in 2021 that included both U.S. Sen. Richard Blumenthal and U.S. Sen. Chris Murphy alongside leading experts in the field, and, just last month, a panel that brought together scholars and advocates to find ways to counter misinformation about gun violence.

“UConn is putting a lot of effort into this challenge,” Dineen says.

Grasso is working with Raissian and Dineen on the national survey of Americans and the Missouri project.

“One of the factors that I hypothesize might be associated with perceived harms and benefits of gun policies and practices is whether a family has experienced interpersonal violence, either as a victim or a witness, and especially involving guns,” Grasso says. “How ‘close’ to violence must one be before the preventative benefits of, let’s say, stricter safe storage policies outweigh the perception of harm to one’s rights and freedoms.”

Next month, ARMS is hosting a workshop with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for UConn researchers to make a plan for disseminating their findings.

“We believe it’s really important that this work becomes usable,” Dineen says. “There are people who work every day to reduce gun violence at UConn, but there are also people working in communities, hospitals, and other places. We’re really interested in how we help UConn get all of the good work that’s being done here to the people who can find it most useful.”

Damage to Individuals, Damage to Communities

The interdisciplinary nature of this work – bringing together public policy specialists and health researchers – is essential for the success of the endeavor. Gun violence isn’t a simple problem – it isn’t even a single problem, considering the different types of harm contained under the umbrella term. Suicide prevention and preventing accidental shootings are different from each other as they are from the problem of gun violence within communities.

“One of the most harmful forms of violence involves the use of guns,” says Grasso. “Not only can gun violence result in needless injury and the senseless loss of lives, the magnitude of collateral damage is huge – with loss and trauma having potential to cause debilitating mental health impairments, including post-traumatic stress, as well as socio-contextual factors that hurt children, families, and communities.”

Understanding the scope of the problem means understanding that different parts of the population are affected in different ways. Older white men have the highest risk of dying in a gun-related suicide, for example, while firearms are now the leading cause of death among children in the U.S.

Reaching those populations requires an understanding of, among other things, how they receive information, and how it circulates within those groups.

Caitlin Elsaesser, associate professor in the School of Social Work, is currently working on research funded by a $250,000 grant from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) into how social media conflict contributes to youth firearm violence and how to develop interventions to address the problem.

The core of Elsaesser’s research is taking the lead from and collaborating closely with youth who have lived experience with gun violence.

Elsaesser has worked closely for a number of years with the Hartford-based COMPASS Youth Collaborative, a nonprofit organization supporting high-risk youth in Connecticut’s capital city. The Hartford region is home to one of the largest wealth gaps in the country, and has experienced increased rates of gun violence in recent years. “What youth and street outreach workers have shared with us in two different studies is that social media is pervasive, and street outreach workers have shared with us that almost all violence they see in the streets has either started on social media or involves social media at some point,” explains Elsaesser, who has conducted significant research on the role of social media conflict in offline violence.

“But I also want to be very clear that social media conflict does not cause violence,” she says. “The cause of violence is access to firearms, and the conditions of concentrated poverty in neighborhoods, like those in Hartford, that stem from structural racism. The experiences that young people have on social media where conflict heats up and leads to conflict offline, is important to understand because it’s part of the sequence. But it’s not the cause.”

The completed first phase of the CDC study involved extensive focus groups with Hartford youth, who detailed the types and causes of stress in their lives as well as the impact they felt from gun violence.

“For example, one young person we spoke to has lost 20 friends in three years to gun violence, and he shared with us that the experience has put him in a depression, that he has stopped having energy to really do anything,” Elsaesser says. “These youth daily demonstrate strength – we see tremendous commitment to their communities and creativity in managing the stress is related to living in neighborhoods with high rates of gun violence, we see incredible commitment to their community. But it is incredibly stressful living in concentrated poverty.”

Phase two of the project will involve a follow up survey, while the third phase will result in tools to be tested by street outreach workers, called Peacebuilders, who are active in the community.

Those tools, Elsaesser says, will be guided by the needs of youth and the outreach workers, many of whom experience a personal impact and loss when someone they know is victimized in the community.

“I collaborate with a board of youth co-researchers who are from the community, and over the course of our collaboration, there were many moments where there was shooting in the community,” she says. “We had open dialogue when these events happen – should we just not meet?

“What they told us is, ‘Listen, this is our reality. It’s shocking to you as someone who’s not from the community, but for us, this is just part of our daily life. Staying engaged is a way to stay hopeful.’”

Jacquelyn Santiago Nazario, CEO of COMPASS Youth Collaborative, says the research has both offered insight into community life, and confirmed the effectiveness of outreach work.

“The work with UConn has been gratifying on many levels,” she says. “It is powerful to note that the youth impacted most by trauma were co-researchers. They gained appreciation for hands-on learning experiences and were also critical in collecting true data from the community. We confirmed that Peacebuilders serve as the consistent mentors that help youth navigate turbulent times.”

An Entire University Responds

No corner of the United States is untouched by gun violence, and Connecticut has suffered badly. The 2012 massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown was a turning point for the public debate over gun violence in the state, with Connecticut policymakers and scholars taking the lead in tackling the problem in its many facets.

“My heart breaks for the people in Uvalde,” says Mary Bernstein, a professor of sociology in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and incoming associate dean of the Graduate School, “but my heart also breaks for the people who I know in New Haven – all of the people who have shared their stories and who have lost children and nephews and nieces and cousins and parents to gun violence.”

As part of an initiative supported by the nonprofit Connecticut Against Gun Violence, Bernstein has helped conduct 10 listening sessions with community members, with the goal of creating a citywide Office of Gun Violence Prevention to help support community efforts to reduce gun violence in the Elm City. She’s now working with collaborators to help build the blueprint for the city’s efforts.

“My role in the project has been to help facilitate these listening sessions with the most impacted communities within New Haven, which are predominantly poor Black and Brown communities, communities that have been impoverished, disinvested in, historically segregated, and discriminated against,” says Bernstein, who is also affiliated with the Sustainable Global Cities Initiative at UConn Hartford. “We’ve been doing these listening sessions to learn from people in the community about how they see their experiences with gun violence, what they think can be done to prevent gun violence, and the impact of the gun violence that they have experienced.”

As good-paying jobs became more difficult to find, as mass incarceration increased, and as cities simultaneously disinvested in those same impacted communities, Bernstein says those communities began to deteriorate. A result of those structural factors and inequities is higher rates of gun violence.

Mary Bernstein, Professor of Sociology, and Associate Dean of The Graduate School at UConn

“When communities deteriorate, when people have little-to-no economic opportunity, they have little-to-no hope,” she says. “A number of young people have really expressed the view a lot of young Black and Brown adolescent males don’t expect to live to the age of 20 or 25, and when you have that level of hopelessness, and when people look at you and think that you are a criminal and you have substandard education, really the only way then to actually survive financially is often to turn to the streets.”

That dynamic needs to be disrupted through sustained action from a variety of institutions, through investment in community resources, and through real efforts to address systemic poverty, racism, and inequity. More focus, she says, is also needed on mental health aftercare, the so-called “yellow tape syndrome.”

“Communities are traumatized by gun violence,” she says. “One of the themes that stands out in the listening sessions is that the constant experience of hearing gunshots, of seeing yellow tape is that you’re constantly reminded of death and violence. In many of these communities, people are afraid to walk down the street. They won’t let their children walk to the corner store, because they’re afraid they might get shot.”

The highly publicized mass shooting incidents of recent days are discouraging, says Bernstein, because many policy solutions to those incidents are known, and the majority of Americans support common-sense gun safety laws. But efforts on the local and state levels to address the devastating effects of community gun violence are a reason for hope.

“Cities and states are creating their own offices of gun violence prevention, and so I think at the local level, in a lot of places, change is happening, and I see that as an incredibly positive opportunity,” Bernstein says. “The fact that New Haven is really taking on this issue, and seems to be committed to having change, having the community involved, putting resources there, that gives me hope.”

At UConn, the community response has ranged from student-led vigils to a halftime tribute by the marching band to Alex Schachter, whose mother and uncle attended the University and who was among the victims of the 2018 massacre at Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

Schachter’s family also endowed a scholarship in his memory, and in the days after the Newtown massacre, the University created a fund to support any siblings of those killed at Sandy Hook, the dependents of adults who also lost their lives, as well as students currently enrolled at the elementary school, who are accepted to attend the University.

From the senior administration to the students of tomorrow, UConn has applied itself to confronting the awful problem of gun violence in American society. The despair and hopelessness that feel so natural after a mass shooting have no place at the University; only a determination to fulfill the mission of a public institution.

“We’re very dedicated to facilitating conversations with policymakers, researchers, journalists, and citizens at large to understand the problem of gun violence and figure out what we can do about it,” Raissian says.

Tom Breen is a former journalist who currently serves as Director of News and Editorial Communications at UConn.

Jaclyn Severance, a news writer at UConn, has worked in communications and public relations in Connecticut for 15 years.

Kimberly Phillips joined UConn as a news writer after more than 20 years of working as a reporter and newspaper editor in Connecticut.