This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the November 2020 election brought out about 155 million voters. That represented 67% of Americans over 18, and it was the highest voter turnout of any modern election.

Americans also set records in the percent and number of people voting early and by mail, continuing a decadeslong trend away from voting only on election day.

That was the good news.

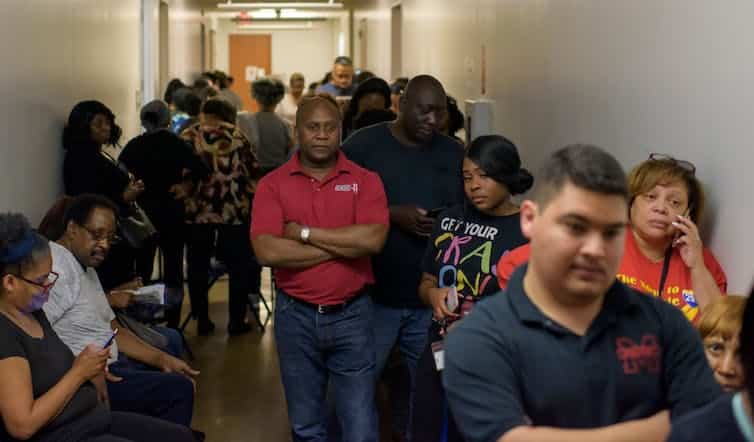

The 2020 elections also saw record numbers of Americans forced to wait longer to vote, partly because of the increased number of voters and the difficulties of safely voting during a lethal pandemic. Tellingly, as in the past, if you waited over 30 minutes to cast a vote, you were more likely to be a low-income Black American.

Since 2012, when more than 5 million Americans were forced to wait longer than an hour to cast their ballots, long waits have become a visible indicator of voting problems.

The Presidential Commission on Election Administration stated in 2014 that “No citizen should have to wait more than 30 minutes to vote.”

Eight years later, that goal is further away than before. Where you are and who you are significantly affect how long it will take you to vote. As well as demanding more time and commitment – including arrangements for child care if needed – long waits can discourage future voting.

Increasing wait times

Average waits nationally increased to 14.3 minutes in 2020 from 10.4 minutes in 2016, a 40% jump. These waits were concentrated in poorer neighborhoods with a higher percentage of nonwhite voters.

A further indication that waiting is a growing problem was its addition in 2022 to the voting inconvenience category by the Cost of Voting Index project, which measures the ease or difficulty of voting in individual states.

While the great majority of Americans waited only a few minutes to vote in 2020, a significant minority did not.

One in 7 voters – 14.3% – waited longer than the 30-minute 2014 goal set by the Presidential Commission on Election Administration, compared with 1 in 12 – 8.3% – in 2016. And 1 in 16 voters – 6.3% – surveyed by the MIT Election Data Science Lab waited over an hour.

Twelve states – including Alabama, Georgia, New York, Indiana and Maryland – exceeded that average. In 2020, Delaware voters reported the highest average wait at 35 minutes – up strikingly from 5 minutes in 2016. South Carolina had the second-longest wait at 30 minutes, up from its nation-leading 20 minutes in 2016.

But the time spent waiting in line to cast a ballot is only the most visible cost of voting.

The full cost not only includes the actual vote, but also the time and effort of registration, staying registered and the nonpartisan counting and administration of the vote. Most election administration officials are partisan figures, though they are expected to administer the election in a nonpartisan manner.

Partisan voting laws

Political parties are using the voting process itself as a way to gain advantage.

Researchers have found a correlation between the number of Republican legislators in a state and the greater the cost to vote will be disproportionately to Black voters.

In at least one state, Florida from 2004 to 2016, as the number of Democratic voters increased in a county, so did the number of voters per poll worker, thus increasing the potential for waiting and other delays.

Strict voter identification laws appear to disproportionately affect minority voters but not overall voter turnout, although the full impact of these laws remains uncertain.

In 2021-22, 21 states passed 42 laws making voting more difficult. Some of those laws include imposing new photo ID requirements, limiting Election Day registration and requiring voters to provide identification numbers when they apply to vote by mail.

On the other side, 25 states passed 62 laws making voting easier. In June 2022, for example, New York Governor Kathy Hochul signed into law the landmark John Lewis Voting Rights Act that created new legal protections against voter suppression, vote dilution and voter intimidation.

Despite the greater number of bills that made voting easier, the restrictive laws were more encompassing, often rolling back successful pandemic-based efforts to encourage early and absentee voting. Despite research showing no partisan advantage to early and absentee voting, restrictive laws were passed primarily in Republican states and expansive laws primarily in Democratic states.

A question of fairness

The effect of these laws on turnout is uncertain, especially if they inspire a “backlash mobilization” or civic education efforts. Lawsuits may block some laws. In early October 2022, a Montana state judge deemed three laws unconstitutional – one that required additional identification if voting with a student ID, another that halted third-party ballot collection and a third that banned same-day voter registration.

The last two laws would have adversely affected Native Americans, who might live 50 miles from a polling place.

In September 2021, the GOP-controlled Texas legislature passed a new election law that restricted early voting, tightened absentee voting, instituted new rules for voter assistance and added criminal penalties for some violations.

One ramification occurred during the 2022 primary, when Texas election officials rejected over 12% of absentee ballots, a huge increase from the normal 1% to 2%.

While rejections equally affected voters in Republican and Democratic Texas primaries, strict rules about who could vote absentee meant most of those disqualified voters were over 65 or had disabilities.

Depending on who was the majority party, Texas Democratic and Republican politicians have long led the nation in making voting difficult for Black citizens since the end of the Civil War, and more recently once Republicans gained power in the 1980s.

In 2020, Republican Governor Greg Abbott restricted ballot drop boxes to only one per county, giving the 4.7 million people in the 1,778 square miles of Harris County, which is 20.3% Black, the same ability to drop off their ballot as the 10,500 people in the 275 square miles of Franklin County, which is 4.8% Black.

Before the ban, Harris County intended to provide 11 ballot boxes for easier access. Abbott claimed he was increasing ballot security, but the reality was that he increased the difficulty for city dwellers, who increasingly lean Democratic and nonwhite, to vote.

Perhaps the country’s most restrictive election law, Georgia’s Election Integrity Act of 2021, reduced mail and early voting while making the State Election Board a more political office. Fulton County, the largest county with over a million people and is 44.7% Black, will be limited to eight ballot drop boxes – all indoors – instead of the usual 38 outdoor drop boxes. In addition, the law banned the county from using mobile voting buses.

Media attention, however, focused on a ban on offering food or water to voters within 150 feet of a polling place or within 25 feet of voters waiting in line. An exception was made for poll workers and election judges who can provide water to voters.

Just as some nonprofits have helped states improve the clarity and legibility of their ballots, so too could similar nonpartisan expertise of resource optimization and supply chain management improve the administration of elections.

Like other state governments, Georgia could minimize the time needed to vote if it provided the resources, training and communication to its staff that administers elections, and thus encourage American citizens to exercise their ability to vote.

“A cornerstone of our election process is fundamental fairness,” Matthew Weil, the Bipartisan Policy Center Elections Project director, stated. “If different people are experiencing the election system, the voting experience, quite unequally, that’s a problem – full stop.”

Jonathan Coopersmith, Professor of History, Texas A&M University